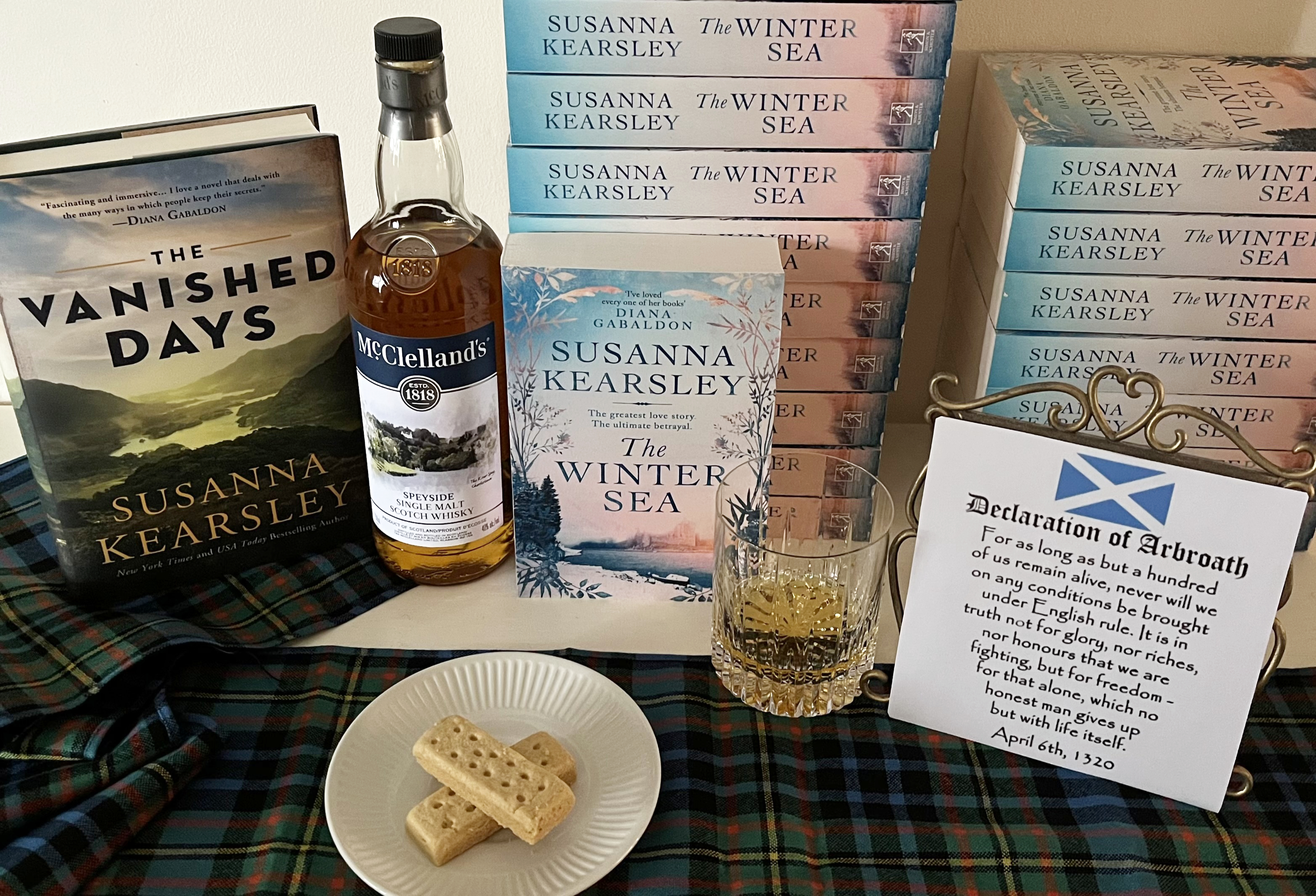

From now till 25 April 2022, my Canadian publishers, Simon & Schuster Canada, are hosting a special sweepstakes giveaway of Scottish gift items (for Canadian entrants only, so sorry). You can learn more by visiting this page!

“There’s no’ a day in a’ the year,

We greet wi’ sic a hearty cheer, —

For Scotia’s sons frae far an’ near,

Their hearts obey,

Tae haud oor patron saint aye dear,

St. Andrew’s Day.”

Those lines are from the poem “St Andrew’s Day” by Robert McLean Calder, a Scotsman who lived here in Canada and in the States for a while in the mid-1800s and later gathered those verses and others into a slim collection of poetry, Hame Songs.

Calder came from Berwickshire in the Borders. He belonged to Duns, where he was born, and was claimed by Polwarth, where he spent the happiest days of his childhood.

I was born in Canada, not far from where he spent his time here. And you’d have to travel back two hundred years or more, by way of Belfast, to meet my own Scottish ancestors who lived close by Kirkcudbright.

Mr Calder was a Scot who lived in Canada. I’m a Canadian with Scottish roots. I don’t belong to Scotland.

In spite of that, the poem “To Exiles” by Neil Munro speaks directly to my soul. Especially the last two verses, and above all else, the last two lines. I will not quote them here, because the poem’s protected by its copyright, but if you haven’t read it I’d encourage you to use the link, and take a moment now to do so. It is unforgettable.

Those last two lines are how I’m made to feel when I’m in Scotland. On my first visit, nearly half a century ago, when I was ten and shy, the people seemed as warm and kind as longtime friends, and each time I’ve returned since then I have been welcomed.

But I don’t belong to Scotland.

When you leave a country, as my people did two hundred years ago, the country moves on, so the pieces of it you preserve are of an older country that’s now gone, and in its place the modern country forges on without you.

Which is why, although I write of Scotland’s past, or let my modern characters move through the landscape as I do, as visitors, I never would presume to state opinions of the country’s present or its future.

Still, when people leave a country, sometimes what they carry with them—those small pieces they preserve—have hidden value.

Like St Andrew’s Day.

St Andrew has been the patron saint of Scotland since at least 1320 (when the Scottish barons sent the Declaration of Arbroath to the Pope asking for his recognition of Robert the Bruce as their king and of Scotland’s independence) and use of his X-shaped cross, the Saltire, as a symbol and flag in the country pre-dates even that.

His day—30 November—became one of the Catholic Church’s festival days in the 7th century, joining other days when people were supposed to rest and do no work, like Christmas and Epiphany and Easter.

But in the 16th century, the Scottish Reformation swept away those Catholic feast days—even Christmas (known as “Yule” in Scotland).

Or at least it tried to.

Some Scots weren’t so keen, apparently, to let go of their “patron saint aye dear”. In Cobbett’s Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings, an entry for 30 November 1686 complains: “Being St. Andrew’s Day, the Papists consecrated, at least initiated, their chapel in the Abbay by holy water, and a sermon preached by Widrington. They bragged this was a great providence, that it fell on the festival dedicated to the patron of Scotland…”

And when Scots had to leave their country…well, they took their patron saint along and celebrated.

On the first day of November, 1698, in what would come to be both one of Scotland’s boldest ventures and most heartbreaking disasters, ships of would-be Scottish colonists dropped anchor in a bay of what we know today as Panama, and what to them was Darien. And on the last day of that month, a clerk of that same colony wrote in his journal: “This being St Andrew’s Day, the Councilors dined on board the Comadore, where Captain Andreas [one of their newly-met native allies] was invited.”

Even when their travels were more profitable, and closer to home, Scots took St Andrew with them, as the newspapers of those times make clear. In the Caledonian Mercury of 8 December 1724, we find reprinted a dispatch from the Flying Post from 1 December that tells us: “Yesterday being St. Andrew’s Day (the Titular Saint of Scotland) the Natives of that Part of Great Britain wore the Cross of that Saint; and the Nobility of the Order of St. Andrew, or the Thistle, made their Appearance at Court in their Green Ribbans…The Society of Scots Gentlemen, who meet here annually on this Day, had a Feast, as usually, and chose Mr. George Middleton their Master for the Year ensuing.”

How long this “Society of Scots Gentlemen” had been meeting annually in London for their St Andrew’s Day feasts, “as usually”, the article doesn’t say, but they’d apparently been doing it awhile.

And five years after this, across the sea in Charleston, another group of Scottish expatriate gentlemen would follow suit and form the first St Andrews Society in 1729.

In Robert McLean Calder’s book Hame Songs, beneath the poem I quoted from at the beginning of this post, he included a note stating: “The above poem was awarded a Gold Medal by the St Andrew’s Society of Ottawa in 1868.”

By the time Mr McLean wrote his poem, St Andrew’s Day had grown to be widely celebrated abroad, wherever Scots had travelled, set down roots, and formed communities, and St Andrew’s Societies—in addition to their charitable activities—provided spaces for Scotsmen to gather, do business and share in their culture.

In late Victorian Scotland, meanwhile, the day was much less of a thing, leading the 19th century author of Scotland and the Scots, Peter Ross, to wonder in his chapter on Anniversaries and Holidays: “Why do the Scotch people in Scotland not observe St Andrew’s Day?” His best guess was that for Scots in Scotland, “There is no need for observing any such landmark, for Scottish patriotism is still active and diligent, and is ever at work in countless ways.”

He’s right, in that it’s nothing but a day. And yet…

For all those people who defied the efforts of the Kirk to stop them celebrating, that day mattered. For those gentlemen who met and feasted every year in London, that day mattered. And for those who, from the furthest corners of the world, remembered every last day of November to wear their Saltire and find another Scot to share a meal with, that day mattered.

And in no small part because they did not break faith with their “patron saint aye dear”, the Scottish Parliament was able fifteen years ago to formally declare St Andrew’s Day a proper holiday, restoring its official status.

As I said, when people leave a country, sometimes what they carry with them—those small pieces they preserve—have hidden value.

It’s like taking a flame from an old hearth and keeping it safe in a lantern, away from the wind and the weather, so you can rekindle that fire when you get where you’re going.

Or light the old flame again, if it ever goes out.

* * * * * * *

To honour the day, here’s a scene from my new novel, set on St. Andrew’s Day:

* * * * * * *

Tuesday, 30 November, 1697

Maggie looked across the water of the firth towards the further shore, her forehead furrowing the way it always did when she felt Lily’s explanations made no sense. ‘But it looks nothing like a road.’

The day was sunny but the wind was brisk, and Maggie leaned back into Lily, seeking shelter. Now that Maggie had turned eight, the top of her fair head exactly reached the height of Lily’s heart.

The symbolism of that was not lost on Lily. With her arms wrapped closely round the little girl, she said, ‘Ye asked me where the Road of Leith was, and I’ve shown ye. It is no more than a stretch of water near the shore where ships may safely lie at anchor.’

From behind them, Captain Gordon said approvingly, ‘That is an excellent description.’

Maggie wriggled free of Lily’s arms and danced around to greet the captain, holding up her doll to show the new blue cloak that Barbara had made for her.

‘Very bonny,’ Captain Gordon said, ‘and perfect for St Andrew’s Day.’ He looked around them at the crowds of people who were gathering and strolling past, awaiting the festivities. ‘Is Mrs Browne not with you?’

Lily shook her head. ‘She said since red hair brings bad luck to ships, and a woman brings more, then a redheaded woman is bound to be very unwelcome today.’

Maggie told him, ‘They are giving a ship a new name.’

‘Aye, so I did hear.’

‘It’s over there,’ said Maggie, pointing out the ship anchored across the firth at Burntisland. ‘Ye see? The second one, with all the blue and gold. It’s twice the size of yours.’

‘A little more than twice, I think. But ships are built for different things,’ the captain said. ‘My ship, like many others in the harbour here, is owned by merchants who employ me as its skipper. Once or twice I may have sailed as far as Spain or Italy, but generally we sail no further than to Holland or to France and home again, and she needs only to be large enough to hold her cargo and my men. ’Tis better she be slight and swift than lumbering and large, in case we’re forced to run from privateers. And sixteen guns are all I need to make someone think twice about pursuing us.’ He nodded at another larger ship that was familiar to them all. ‘Now, something like the Royal William is completely different. She belongs to our Scots navy and the crown, and has a duty to patrol our coast and give an escort to the smaller merchant ships, like mine, when we are travelling in convoy. That’s why she’s a larger ship with thirty-two guns, and can carry troops of soldiers if she’s called upon to keep us safe.’

Maggie pointed out that, if he were the captain of the Royal William, he could wear a fine blue coat. ‘Ye would be very handsome.’

‘Thank you. But then I’d be bound to sail wherever the king told me to, and nowhere else. So while I do agree it would be fine to have a ship so grand, I’ll steer the course I have a while longer, if it’s all the same to you, and bide my time till we’ve a Stewart on the throne again.’

Lily said, ‘You may be waiting a long time, considering the terms of peace.’ The ink was barely dry upon the treaties lately signed to end the war with France, and one of the conditions that had been agreed to was that the French king should recognize King William as the rightful British monarch, and deny King James. This had come as a great blow to the Jacobites, and must have been an insult to King James as well, considering the French king was his cousin.

Gordon shrugged. ‘Peace rarely lasts, and treaties are but words on paper. King William is not well liked and has no children, so I’ll wager before long the throne will pass to Princess Anne,’ he said. ‘And she’s a Stewart.’

Maggie was not interested in politics. ‘You did forget the two new ships at Burntisland.’ She’d been obsessed with those ships since the first of them, the Caledonia, had slipped in upon the tide last week, resplendent in her show of red and gold and blue, the wind filling the sails on her three tall masts as she fired the forward-mounted cannon in her bow to hail the townspeople. When she had first been spotted in the firth, the word had spread, so there’d been time enough for Lily to bring Maggie to the pier to watch the great ship gliding past, and to hear that cannon, and to hear it answered by the booming guns of Edinburgh’s great castle, high atop its rock.

The second of the ships, arriving yesterday, might well have been the first one’s twin.

‘Why are they both so big?’ asked Maggie.

‘Well,’ said Captain Gordon, ‘those belong to our own African Company.’

‘What’s that?’

‘Well, in full it’s called “The Company of Scotland Trading to Africa and the Indies”, but that’s far too long to say in conversation, would you not agree? Aye, so would I. So then, our African Company is a brave new venture with an aim to raise our country to the level of the English and the Dutch – both of those countries have rich companies that trade to the East Indies and to even further shores where there are markets for their goods. And,’ he told Maggie, ‘they have colonies.’

She asked him, ‘What’s a colony?’

He had to think about the definition. ‘It’s a small piece of your own country that you plant in a far-off land,’ was what he finally settled on. ‘You build up towns, and farms, and roads, and people go to live there.’

‘What if someone’s living there already?’

‘If you have enough men, you could always take the land by force. That’s what the Dutch did at Batavia and their other colonies in the East Indies.’

Maggie disapproved. ‘That is not nice.’

‘No, you’re right, it’s not.’ The captain half-smiled in the way men do when a child’s simple honesty reminds them of their conscience. ‘And our African Company agrees with you, which is why they plan to found a colony for Scotland on land that no other European nation has yet claimed, and if our settlers do find natives there, we must get their consent before we build.’

That suited Maggie better. ‘Where is the new colony to be?’

‘Nobody knows. It is a secret.’

‘Why?’

‘Because,’ he said, ‘the English and the Dutch do have their companies that sail to the East Indies, as I said, and they are jealous of our own, and do not wish to share the seas, and if they knew where we did mean to plant our colony, they might make trouble.’

Lily knew King William had been making trouble, too. Although he’d given his consent to the formation of the African Company and its aims, he’d since done all he could to prevent its success. It was by King William’s order that no English or Dutch investors had subscribed to the Company, and the English merchants who had at first been so enthusiastically involved in the venture had withdrawn their support for fear of losing the king’s favour, leaving Scotland alone to carry the financial burden of raising enough capital.

But the people of Scotland, across all social ranks and religions, had risen to the challenge and subscribed their names into the company’s book, and the beautiful ships now anchored in the firth were a testament to what could be achieved when Scots looked past the things that did divide them and pursued a common dream.

Captain Gordon said to Maggie, ‘That is why those ships are larger. Because they must travel very far. They need more sail, and must be big enough to carry all the things they’ll need to trade, and build the towns, and transport the first people who will live there. And because they’re going to an unknown place, with unknown dangers, they must have more guns. I have not counted yet how many these ships have, but—’

‘Fifty-six,’ said Maggie. ‘I did count them when the Instauration came in yesterday.’

‘Did you indeed?’ The captain grinned. ‘I think, when you are grown, my first mate will need to be careful, lest I hire you instead. That is a big word for a small lass – Instauration. Do you know its meaning? No? It means the restoration of a thing that has been cast aside to fall into a state of disrepair, like our poor country, or our pride, which both do need to be renewed.’

‘But they are changing it,’ said Maggie.

‘Aye. To the St Andrew, which is also a fine name for a ship of Scotland, and on this day above all others.’

Maggie nodded her agreement, for she knew about the patron saint of Scotland, and she’d always liked the festive nature of his feast day. ‘I’m wearing my saltire today,’ she told the captain, showing him the diagonal X-shaped St Andrew’s cross pinned to her plaid. ‘And so is Dolly, only hers is made of wire. Henry made it.’

Captain Gordon bent to give it his appraisal. ‘Henry’s very clever.’

Henry, having just come up to join them, laughed. ‘Ye’d be alone in thinking that, but I will take the compliment.’ He greeted Captain Gordon, who had noticed something else on Dolly.

With a smile, the captain said to Maggie, ‘Dolly has a new admirer, I perceive. Who gave her this?’ He touched the second wire brooch, shaped like a heart, meant to be hidden underneath the doll’s blue cloak.

Conspiratorially, Henry leaned closer and told him, ‘That is a great mystery, we’re not meant to know.’

You can learn more about The Vanished Days, read the opening chapters for free, order the American edition, or pre-order the Canadian and British editions, by visiting the book’s page here on my website. If you’re here in Canada, don’t forget to save your pre-order receipt so you can enter the publisher’s sweepstakes!

0 Comments